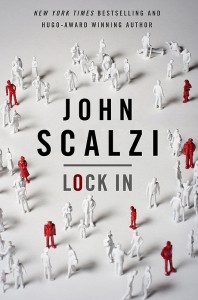

Author: John Scalzi

Publisher: Tor Books on August 26. 2014

Audio: Audible Studios, narrated by Wil Wheaton

Source: Bought

Not too long from today, a new, highly contagious virus makes its way across the globe. Most who get sick experience nothing worse than flu, fever, and headaches. View Spoiler »

Chris Shane is having a rough week. As a rookie FBI agent, he’s pretty ill-equipped to handle being shot at, blown up, and constantly quizzed by his new partner. Thankfully he spends most of his days with his consciousness inside a metal conduit called a threep, a humanoid robot. Keeps the damage from all those explosions minimal, you know?

Shane has Haden’s Syndrome, an extremely virulent strain of the flu that can result in a person being “locked in,” leaving their body paralyzed while their mind is fully functional. Since his job requires him to have a physical presence, Shane uses a threep for the majority of Lock In. The easiest way to conceptualize a threep is as a car: it’s a vehicle that enables someone (or at least their consciousness) to go places they might not be able to otherwise. And much like cars, threeps have become status symbols. The more elaborate your threep, the more wealthy and powerful the Haden inside it is. Because of threep culture, we have very little idea what Hadens look like, and it isn’t until the end of the novel that some information about Chris’ appearance is disclosed. Since I don’t want to give it away, I’ll just say that I was very impressed that Scalzi went this route.

Some people struck with Haden’s Syndrome survived without being locked in and became integrators. Integrators allow people who are locked in to use their bodies as a sort of vehicle, experiencing a sort of mind meld where the locked in person can use and control the integrator’s body to…well, integrate into physical society. The central plot line of Lock In centres around the suspicious deaths of several integrators and the mounting evidence that they’re connected to the looming Hadens’ rights protest set to launch on Washington.

Integrators often suffer psychological damage from having so many different people in their heads (duh), and Shane’s new partner Leslie Vann is no exception. A former Integrator, Vann is clearly emotionally unstable and self-medicates with alcohol, cigarettes, and sex. Add to that the fact that she thumbs her nose at proper police procedure and she’s your typical stock character damaged law enforcement agent. Except, of course, that the majority of these stock characters are men. John Scalzi challenges stereotypes and reader expectations with many of his characters, and I couldn’t get enough of it.

The development of Haden’s culture was probably one of the strongest elements of the novel. When millions of people begin experiencing a new way of living, of course a unique culture reflecting that lifestyle begins to emerge. I think Scalzi showed real sensitivity when he emphasized the fact that Hadens are not a homogenous group; some choose to integrate themselves into the physical world using threeps while others choose to live in an online space called the Agora. This latter lifestyle is most obviously represented by Cassandra Bell, a militant Hadens activist who’s responsible for organizing the aforemetnioned march on Washington for Hadens’ rights. For those of you who know your political history, Cassandra Bell is kind of like the Emma Goldman of Lock In: a radical whose support is growing by the hour…and a woman who may or may not have qualms about bombing corporate buildings.

In addition to radical politics, there’s also an amazing amount of diversity in Lock In. Obviously the discussion of people living with disabilities is at the forefront of the novel, not something you see everyday in SFF. There’s also racial and sexual diversity, as The Navajo Nation has a central role in Shane and Vann’s investigation, and the CEO of a major Haden corporation is openly gay. I also really appreciated the ambiguity surrounding Vann’s sexuality – despite her frequent gripes about how the investigation is cutting into her sexy times, Vann never offers up a gender for her sexual partners. I cannot praise Scalzi enough for the ease with which he incorporates underrepresented populations into Lock In. Seriously man, gold star.

But Lock In in’t just a shining example of representation-done-right in SFF, it’s also pretty damn funny. Scalzi has a wonderful deadpan humour that plays out beautifully in the interactions between Shane and Vann. I listened to this on audiobook, and I have to say that Wil Wheaton did a great job as Shane. He definitely has the delivery down pat. I wasn’t prepared for just how funny it was, and made the rookie mistake of listening to it as I walked to and from campus; unfortunately many people were treated with the wonderful sight of me snortling (snorting and chortling) into my tea in broad daylight. Thanks a lot, Scalzi.

Many of my blogging buds have said that John Scalzi’s books are a great choice for people looking to jump into more science fiction, and after reading Lock In, I completely agree. Considering how technical some elements were, I found Lock In very easy to follow. And let me be the first to tell you that I’m not known for my tech skills. Nevertheless, I had no trouble envisioning neural networks and the liminal spaces created within the Agora; if you’ve been reticent about science fiction because of all the jargon and emphasis on tech but still want to give it a try, Lock In is the perfect way to dip your toes in!

As for me? I’ll be dipping my toes into John Scalzi’s back catalogue, ASAP.